The vanishing present

With the accelerated pace of contemporary life, brought about by urbanisation, new technologies, cheap travel or what has been termed globalisation, space is expanding whereas time is shrinking. Svetlana Boym suggests this has led to a contemporary nostalgia that is not only about the past but ‘the vanishing present.’ Rather than a longing for place, there is a reflective yearning for a different time, or ‘the slower rhythms of our dreams’.1

This ‘vanishing present’ has been a constant theme in Jennifer Trouton’s work. From the erosion of domestic skills passed down from mother to daughter in Select Your Pattern Pieces According to the View You Have Chosen (2000), to objects fast becoming obsolete in Looking At The Overlooked (2002), to the transformation of the rural Irish landscape in Re(collection) (2006), she has observed and preserved their haunting mnemonic associations.

Despite numerous accolades, most recently receiving The Keating/McLaughlin Award at the 181st RHA annual exhibition, as a female artist whose subject is the domestic there is always the danger of accusations of perpetuating it as an essentialist feminine space. For Trouton her insistence on painting in a representational, academic, trompe l’oeil style, either incorporated into multi media pieces or as stand-alone works, could also be viewed as traditionalist. However, these are deliberate considerations to create an ‘off-modern’ or ‘inbetween’ aesthetic that straddles time and space. As Nikos Papastergiadis puts it, ‘For centuries, the use of the trompe l’oeil has been a powerful example of the way art refers to the signs of everyday life but also displaces the appearance of things. It can simulate the appearance of ordinary things and also point to what Gombrich called “an ensemble of possible states”.’ 2

In her new exhibition Post, a prefix that opens a plethora of possibilities – feminist, industrial, colonial – it implies something that is after, or subsequent to, the present. Furthermore it suggests communication, employment and news. The juxtaposition of images and media trigger a series of intersections for enquiries between concepts such as urban/rural, home/abroad, local/global, inside/outside, real/unreal, imaginary/factual, authenticity/illusionism, factory made/handmade, wealth/poverty, painting/time based media, tradition/innovation, which respond to the temporal and spatial transformations that have occurred in relation to art making, emigration, journeying and home.

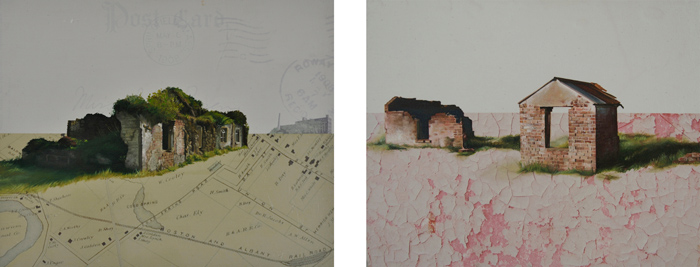

Regimented in size and form to resemble postcards, the first series of multiples subverts the idealised vision of rural Ireland that is often used to promote the country as a tourist destination. In reality this hyperIrishness is a false portrayal. The abandoned dwellings merging into the landscape, seemingly unimportant, innocuous, crumbling and forgotten are the ghosts of that consumerist promise. (Grass is always greener Series number 11,24 x 23 cm, oil, lazertran on board, 2011)

Once the hub of family life, modernity and communication, now the outside world enters the home via new technology without call for face-to-face interchange. By metaphorically depicting the ruination of traditional life via the architectural disintegration of what once was a home cum Post Office, a stark contrast is set up in relation to the fast communication of the internet and vanishing home life.

The merging of inside and outside spaces and traces of time are presented compositionally by a series of markings that have been copied or traced onto the boards. Cursive writing, postmarks, family photographs, inventories, cracked porcelain and peeling wallpaper signify spectral remnants. These are further inferred by the gentle opaque palette of translucent pink and blue hues which give the effect of the past haunting the present. Gramsci’s idea that identity is linked to the need to make an inventory is a possible reading, as these houses were originally the home of her maternal ancestors.3

Benjamin also wrote that to live is to leave traces, and in modernity were accentuated in the private space.4 Trouton presents these crossings between the public and the private space by mixing media, thus commenting on contemporary spatial changes where all boundaries are being redefined. (‘Grass is always greener’ Series number 16,24 x 23cm, oil, lazertran on board, 2011)

Punctuated by two large pieces incorporating fragments from the previous works, the viewer is confronted with a greater expanse of imagery to scrutinise the mourning of the passage of time. Like old sepia photographs, dark and brooding, they are centrally lit to draw the gaze to the centre of the subject. (Plate’ Over there’ oil, Lazertran on Board 40 x 40 cm, , 2011)

Moving from multi-media to painting, sumptuous floral silks fill the entire compositions, temptingly textural and reminiscent of another time when artistry was defined in very different terms. (Plate Your huddled masses, 40 x 45cm, oil on linen, 2011) In contrast, a series of wallpaper imagery in earthy tones, depicting repetitive disintegrating houses and industrial machinery subverts the idea of cosy affluent interiors. The imagined hopes of a better life in the New World blurring into the reality of toil that often accompanies the act of emigration.

Hung together, these create a conversation between the many universes. (Plate’ No place like Home’, 40 x 45cm, oil on linen, 2011)

In Shift these elements are brought together within one large canvas. On the surface this is a grand artistic demonstration of dazzling drapes. However, as the cover slips, wallpaper is revealed printed with the houses of home to subtly shatter the initial vision. (Plate Shift, oil on canvas,120 x76cm).

Trouton’s process is itself a study in time. By presenting exquisite illusionism and ‘skill’ and quick computerised visual manipulations the artist plays with the viewer, who, consciously or not, is confronted with conceptual complexities which, like her subjects, might be overlooked. Rather than the pejorative, literal associations the domestic and nostalgia traditionally convey, Trouton’s new work is an intelligent, lateral exploration of both, which requires looking from many directions and between many spaces.

1 Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 352.

2 Nikos Papastergiadis, Spatial Aesthetics: Art, Place and the Everyday (London:Rivers Oram, 2006), 62.

3 Ibid, 61.

4 Walter Benjamin, ‘Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century’ in Reflections, ed. Peter Demetz, trans. Edmund Jephott (New York: Schocken Books, 1986), 146-162.

Irish Arts Review, Autumn 2011

Jane Humphries is a PhD candidate at TRIARC, Trinity College Dublin