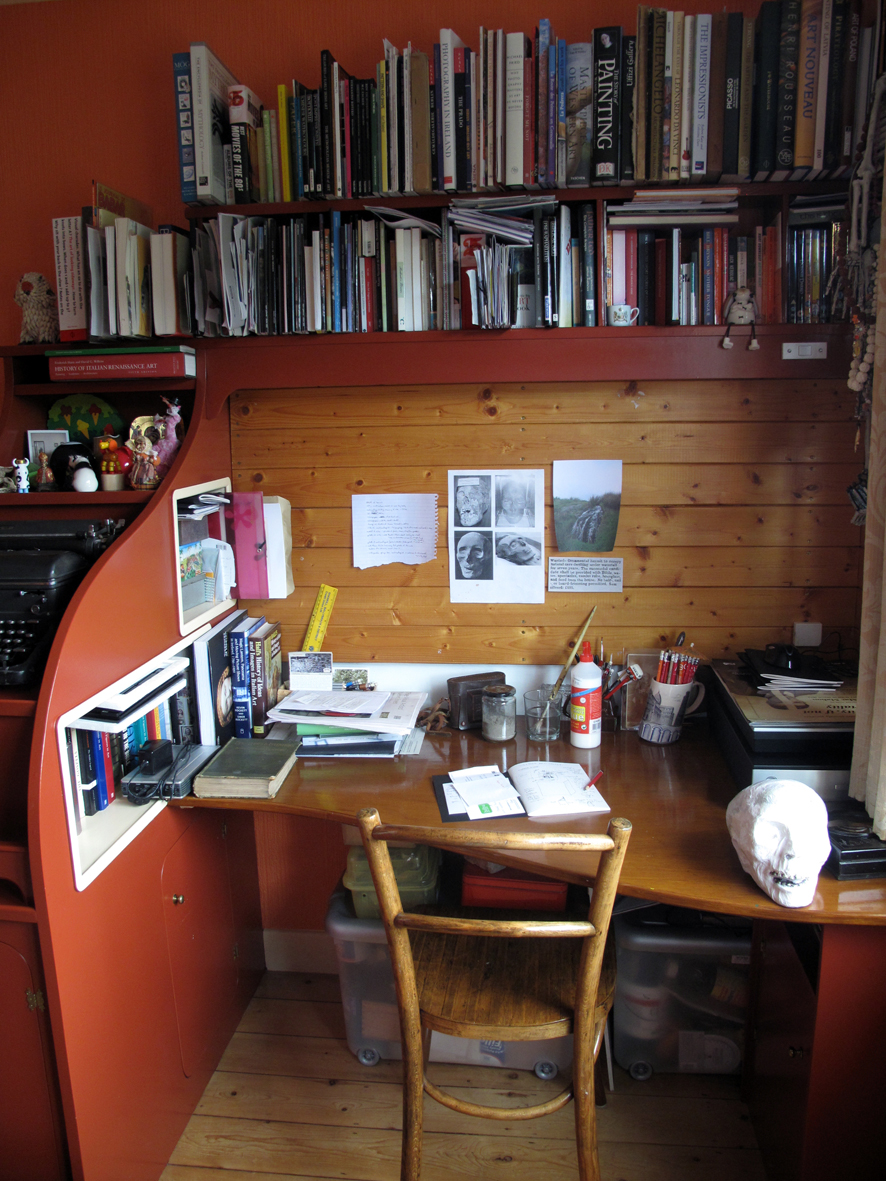

Sabina MacMahon is interested in how narratives translate into pictures and how, very often, there are several stories behind one image or object. She works from her studio at her home in Dublin.

Sabina works mostly with found objects which she reinvents to form completely new stories and histories. These found objects exist in many different forms and Sabina has often used old family photographs to depict the lives of various saints and biblical characters. Earlier this year, she exhibited new work depicting Saint Denis, who is the patron saint of Paris, in the Alliance Française in Dublin. She had some photographs of her grandparents while on their honeymoon in Paris and she restructured these images to create a new story. This took the form of St. Denis Taking a Photograph of Himself and St. Genevieve in the Jardins des Tuileries. As with much of Sabina’s work, the narrative of the story we see is an impossibility but because it is portrayed through a photograph, a photograph that was evidently taken before the availability of computers and programmes like Photoshop, it somehow seems more believable.

Sabina is interested in religious paintings that date from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and how in these paintings certain saints can be identified by what they are carrying, how they are posed or who they are with. She said this “symbolic pictorial language” used to be common knowledge and most people would have known immediately what saint was being portrayed, but now people are not as familiar with some of the lesser known saints. St. Denis is often depicted with St. Genevieve and can be recognised in religious scenes because he carries his head around with him. St. Denis was executed by beheading and after his head was chopped off he is said to have picked it up and walked ten kilometres preaching a sermon all the way.

The images that Sabina constructs are not a comment on religion itself. What she is interested in is how traditional religious imagery illustrates very elaborate and dramatic scenes and often unbelievable or impossible situations. She is interested in how they were created in order to tell the stories of particular saints or religious people and the fact that they were presented as illustrations of real happenings. Sabina finds it appealing that before photography, painters could paint any story they liked and it was commonly accepted by the viewer as being an accurate depiction of what had happened. This led her to start experimenting with found photographs and how people now see this instinctively as the ‘real real’.

She began to play with this idea and through the reconstruction of old family photographs new stories started to emerge. She has depicted many different saints, biblical characters and some figures from Greek mythology by reworking the photographs.

At the root of Sabina’s work is the attempt to make people believe that what she is presenting is real or true.

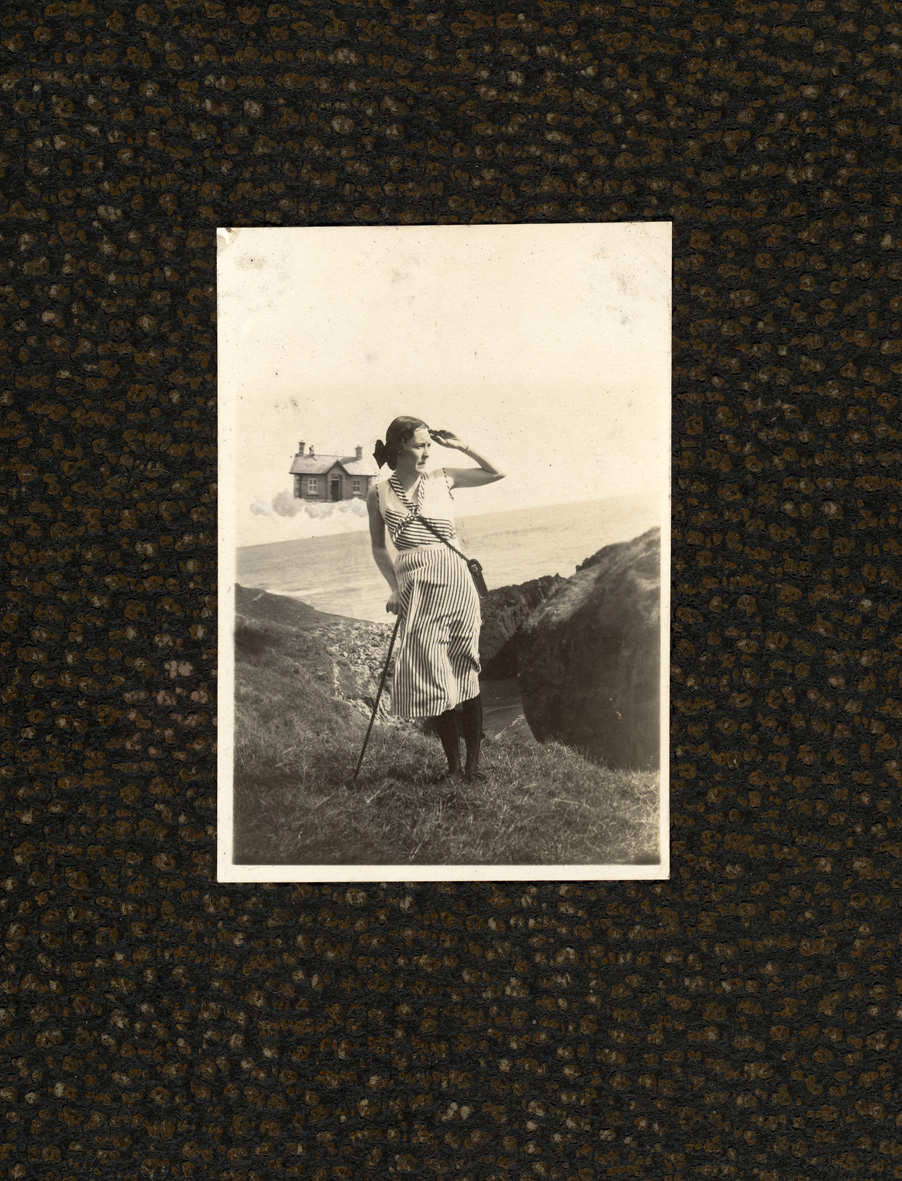

This is evident in some work she made for a “fictional museum exhibition” entitled The Transport of the Holy House of Loreto at The Joinery in Dublin in 2010. For this exhibition Sabina told the story of how the Holy House of Loreto had been seen floating over various locations in Ireland in the 1920s. The Holy House of Loreto is said to be the birthplace and childhood home of Our Lady. It was originally located in Nazareth but came under threat during the Crusades and angels miraculously transported the house to safety, eventually leaving it at its current location in Loreto, Italy. Sabina decided to tell the ‘lesser known’ story of how the house had been seen floating on clouds with the Virgin Mary sitting on the roof over numerous locations across Ireland on the 10th of May 1921.

She presented a group of photographs as recently uncovered documentation which ‘proved’ that this miraculous event actually took place. The information panel that accompanied the photographs described them as being ordinary snapshots of everyday life in Ireland in the 1920s. The main subject of the photograph is totally unaware of what is happening behind them, the photograph just happened to have been taken at the right moment so as to capture the flying house in the background.

As with most of Sabina’s work there was an additional story to back up this photographic evidence. A brick that was found in someone’s back garden on the same day the house was seen in the Irish skies was traced back to the original site of the Holy House of Loreto using scientific testing. This was then presented as further proof that it was in fact this sacred house that people had seen.

In fact the brick displayed as a holy relic was one Sabina had found in the gallery where she works, located in an 18th century Georgian house in Dublin, while reconstructive building was being carried out. She said “increasingly the objects I use in my work hold some kind of personal meaning for me and have real histories that are known, for the most part, only to me.”

Sabina has recently started to expand her use of materials and found objects. In an exhibition last year, entitled Longevity, if not immortality, she exhibited a large stone in a glass display case, similar to one you might see in a museum. This stone, her written description told the viewer, was used to stone St. Stephen to death shortly after Jesus’ Crucifixion. Written documentation displayed beside the artefact told the story of how the stone had been found in the drawer of a desk in an antique shop in London. It was found with a small piece of paper on which had been handwritten ‘This stone was used in the martyrdom of St. Stephen’. Relics are often displayed with handwritten notes to demonstrate their authenticity.

In fact, Sabina had found the stone last year while on a residency at Cow House Studios in Co. Wexford. One of the dogs living at the studios was fond of digging up large stones and leaving them lying around. So Sabina decided to create a more elaborate back story for one particular stone, elevating it to the status of an artefact of great historical significance.

It became apparent to Sabina that the way in which work like this was presented was important to its reading and had an impact on the legitimacy of her stories. As a result she has become interested in museum practice and display as a way of giving a sense of credibility to her stories. She has begun to consider everything commonly seen in a museum as being significant to the display of this kind of work, right down to the presence of humidity control machines and the availability of audio guides. She will be developing work around this concept for an upcoming exhibition that will re-imagine the history of the Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown area.

At the moment Sabina is continuing to work with the idea of a found object. She is currently creating a ‘found’ skull by building on top of a plastic Halloween skull with papier-mâché and other materials. She said she is interested in making objects and pictures herself but presenting them as pre-existing things that she has collected.

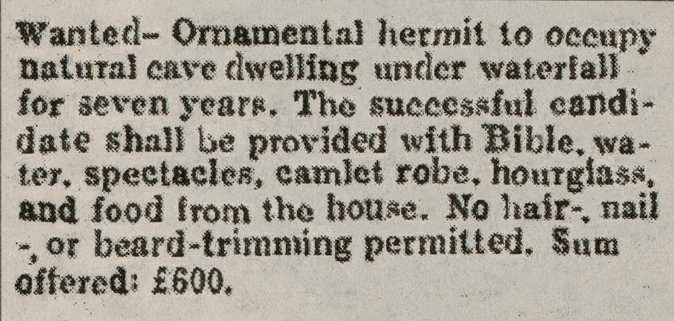

This skull will be displayed as the remains of an ‘ornamental hermit’ found in a cave in Co. Wexford. Sabina told me about a trend in England during the 18th century where the landed gentry began the practice of employing men to live on the grounds of their estates like hermits for the enjoyment of their guests. Sabina liked the idea that this practice may have made its way to Ireland and that this skull could be the ‘proof’ of it. As part of the supporting material for this work she has imagined an advert that could have been put out in a local newspaper looking for applicants for the post of ornamental hermit for a fictional estate in Wexford.

Along with the classified newspaper advert and some additional background information, professionally displayed, this skull might conceivably become an ‘artefact’ proving that the strange practice of ornamental hermitry made its way over to Ireland from 18th century England.

From the studio of…

From the studio of… is an online journal which presents the work of contemporary visual artists as seen in their studios.